The warmth of concrete

While in the inter-war period concrete, considered to lack nobility, was often concealed under a coating or facing, it is now shamelessly flaunted. Left in an unsurfaced exposed state, it retains the imprint of the wooden planks of its mould.

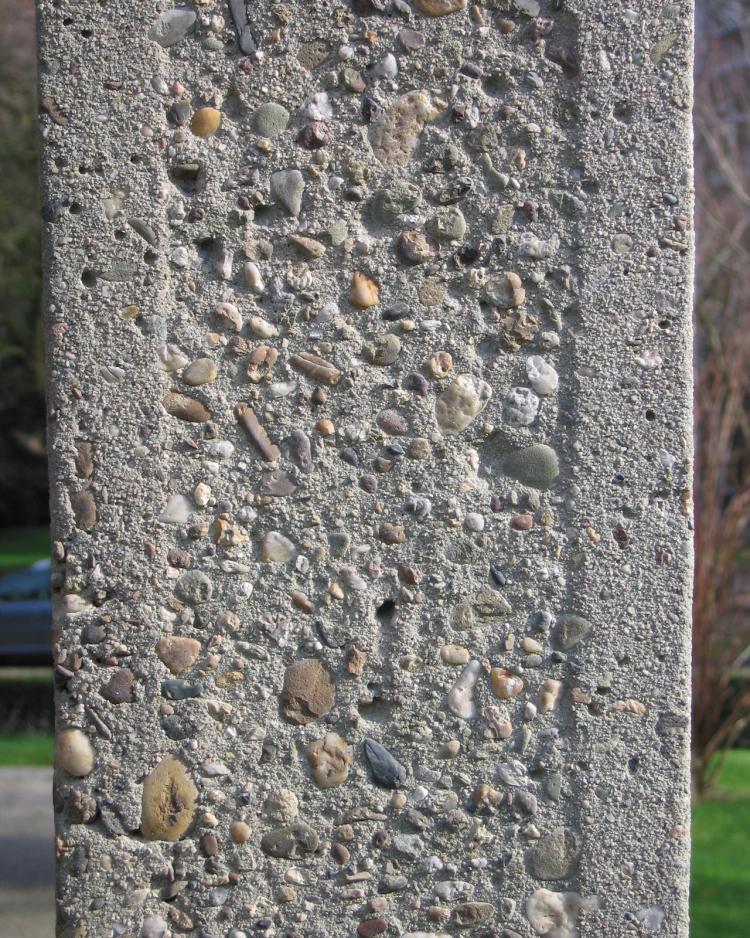

Bush hammered or washed concrete reveals the gravel in its cement.